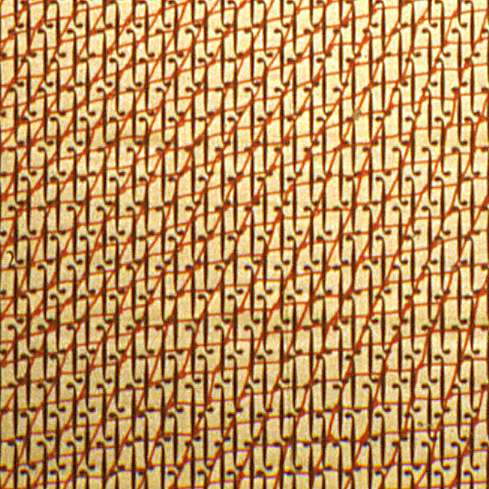

Aiming LowBy Fred CamperPost-Pop, Post-Pictures at the David and Alfred Smart Museum of Art, through September 21 In the collection of the Whitney Museum of American Art is a rare recent example of history painting: Mark Tansey's The Triumph of the New York School, an impressive battlefield scene in which a group of defeated generals--original European modernists like Picasso, Matisse, and Leger--appears to be surrendering to the victorious painters of the New York School: Pollock, Rothko, de Kooning. Amusingly illustrating a dominant cultural conceit, Tansey literalizes the oft-noted passage of art-world leadership from Paris to New York after World War II. But he also parodies the idea that making art is akin to making war. These two generations of artists were men (and they were mostly men) who wanted it all: each aimed not only to express the totality of his consciousness but to change the viewer profoundly. Often seen as a kind of macho posturing, this attitude today is much in retreat. Artists' goals are far less grand; their terrain is no longer the great inner battlefields of Mondrian and Rothko. But the best such recent work redefines what terrain we humans should claim. As curator Courtenay Smith says of the 11 young painters (several from Chicago) in "Post-Pop, Post-Pictures" at the Smart Museum, their work is "closer to the consumer rituals of Martha Stewart's recipes for living than Jackson Pollock's transcendentalist splashes." What surprised me was how much I liked the exhibit: almost every one of the 23 pieces is at least highly pleasurable to look at. Michelle Grabner paints abstract patterns borrowed from product design lovingly enough to personalize them. The allover pattern of interlocked zigzagging bands of yellow and brown dots in Two Yellow Weave could be a sweater design except that it's so painterly: the blobs and splotches give each band a dynamic variety in delicate contrast with the repetition of the zigzag patterns. The green field of Kitchen Wall is filled with a pattern of tiny diamonds, each made of four dots. Though Grabner may be referring to wallpaper, her rather delicate and insubstantial hand-painted dots give the pattern the ethereality of very faded wallpaper--or of a mental image. The four bright, happy abstract paintings by Amy Wheeler, together called "Compacted Closet" but with individual titles as well, reject the idea of the essential shape so key to earlier abstract painters. Each panel of the diptych Organized Shelf (Folded) shows a stack of cheerfully multicolored inverted gentle Vs or similar convex curves. The way Wheeler's stacks connect geometrical Vs and gentle curves suggests antiformalism: Mondrian would no more have painted a curve than Rothko would have painted a geometrical V. But Wheeler finds no great meaning in differences between forms. Indeed, the title of her diptych Good Outfit (Prada Skirt With Barneys Sweater) implies acceptance of whatever our mass culture gives us: in the center of each panel is a single shape, again filled with zigzag patterns, whose curved edges suggest a television screen. I also thought of TV screens in three of

Rebecca Morris's four pictures, whose overlapping

rectangles have similarly rounded edges. In contrast

to the sharp rectangular corners of a cinema

image--which give it a certain absoluteness and

authority and set it off against the rest of one's

visual field--the more curvilinear television screen

blends in with the surrounding room. Morris's

pleasing roundish rectangles have a similar effect;

eliminating the distinctions between various shapes,

she creates a field one can travel through

untroubled. Unlike Mondrian and Rothko--who both

felt they'd discovered essential shapes revealing

some deep inner truth of the universe, which

contributed to the superficially repetitious style

of their mature work--Morris and the other painters

in this show find no cosmic significance in shapes.

They seek not absoluteness but something much closer

to our daily world: shapes and images that are

pleasant to live with, such as better-than-average

kitchen wallpaper and closets full of "good"

sweaters.

This show was tied together for me by the artist whose work comes last, Mark Ottens. His untitled installation is an arrangement of 19 acrylic paintings on the wall; they vary from geometric abstractions so bright they resemble cartoons to depictions of cartoonish figures--in one, rabbits with greenish heads are covered with a pattern of orange and blue dots like M&Ms. This playful work, whose varied and inventive designs produce surprise, is a lot of fun: one can never predict what Ottens will do. But after looking at the installation for a while I realized that, despite their brightness, the paintings had a curiously cool and even effect: there was little difference in emotional tone between the green bunnies and the repeating stripes. This sameness reveals the limitations of such art: in some ways it isn't trying to accomplish much. The search for essential forms has been replaced by a TV-viewer-like acceptance of whatever passes before the eyes, all of which seems ultimately as alike as the programs one encounters channel surfing. The battlefield of art has narrowed from a whole landscape, whether physical or mental, to a kitchen wall or doodles on a legal pad. Though I enjoyed this exhibition, a half hour after I'd left I was hungry again. Art accompanying story in printed newspaper (not available in this archive): "Coincidental Chain of Events" by David Szafranski; "Farewell" by Michal Herman. |

Though Tom

Moody and David Szafranski produced the largest

works in the show, recalling the "heroic" paintings

of the abstract expressionists, their materials and

subjects announce different goals. Szafranski's

Though Tom

Moody and David Szafranski produced the largest

works in the show, recalling the "heroic" paintings

of the abstract expressionists, their materials and

subjects announce different goals. Szafranski's